Climate change is going to affect many aspects of our lives like for example the spread of zoonotic infectious diseases. This creates new challenges for science as well as for the public health sector. A series of three workshops of the Zoonoses Platform in cooperation with the Academy for Public Health in Düsseldorf is therefore dedicated to the topic "Climate Change and Zoonoses". The first part of the series addressed the future challenges posed by climate change with regard to zoonoses in general. The second part focused on a newcomer to Germany: the mosquito-borne West Nile virus.

Some zoonoses are transmitted between animals and humans via so-called vectors. These vectors can be arthropods such as ticks or mosquitoes. West Nile virus is a mosquito-borne zoonoses. The warm summers and winters of the past three years have allowed this virus to establish itself in Germany. How did it come about? What does it mean for animal and human health? And how can we deal with this new zoonosis in Germany in the future? These and other questions were addressed by Dr. Ute Ziegler, Head of the National Reference Laboratory for West Nile Virus Diseases in Birds and Horses at the Friedrich-Loeffler-Institute, and Dr. Birte Pantenburg, employee at the Health Department in Leipzig, in their presentations at the online workshop on April 20, 2021.

Migratory birds as transfer hosts for global spread

The infection cycle of West Nile virus takes place primarily between mosquitoes and wild birds. Via so-called bridge vectors, host-unspecific mosquito species that suck blood from different species, transmission of the virus to a variety of mammal species can occur. These include so-called "dead-end hosts" that can become infected with the virus but do not pass it on themselves. These include humans and horses, as Dr. Ziegler discussed in the workshop. Migratory birds can spread the virus over long distances. West Nile virus was first detected in Uganda in 1937. Since the 1950s, it has been found in south/southeast Europe. In 1999, it was introduced into the U.S., where it spread rapidly across the country within a few years, causing deaths in birds, horses, and humans.

Arrival in Germany - "Only a question of time"

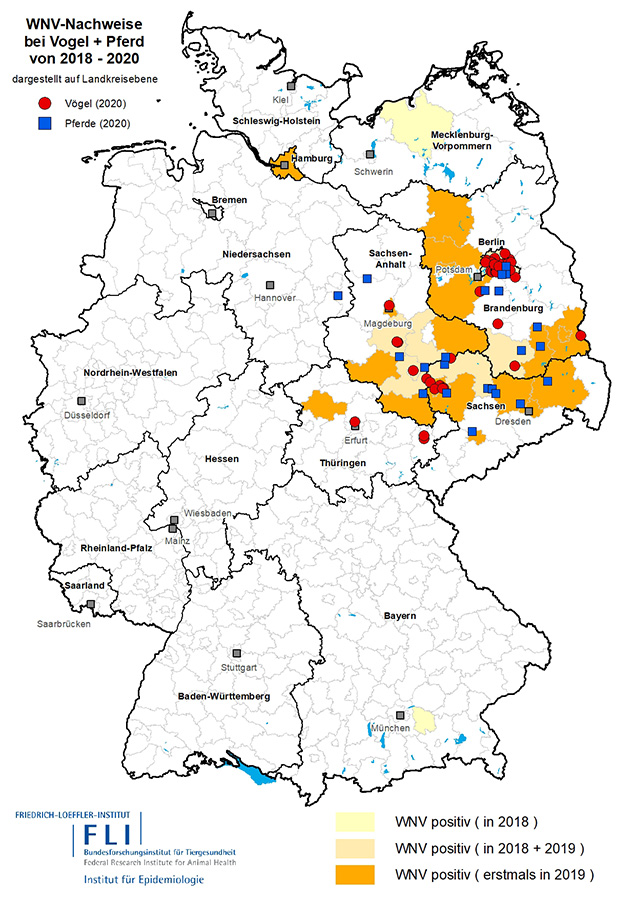

For vector-borne diseases to become established in a place, three important basic conditions are needed: the presence of the pathogen, susceptible hosts, and suitable environmental conditions, as Dr. Ziegler explained. Due to climate change, environmental conditions are changing in many places. After a mild winter and a particularly warm summer in 2018, the first West Nile virus infections occurred in zoo and wild birds (12 cases) and horses (2 cases) in Germany. The rapid detection of the first cases in Germany was due in part to wild bird monitoring for West Nile and Usutu virus, which had already been established since 2010. "It was clear to us that it would only be a matter of time before West Nile virus also appeared in Germany," said Dr. Ziegler. "For this reason, we established the wild bird network early on. This allowed us to sample closely and detect any introduction of the virus early on." In 2019, due to the monitoring 112 cases in birds and horses could be detected. In 2020, there were another 86 cases.

Fig.1: Confirmed West Nile virus infections in birds and horses in Germany in 2020; Map: Friedrich-Loeffler-Institut

The endemic area of the infections is found in eastern Germany. Here, introduction probably occurred via migratory birds. In recent years, the vector and pathogen were then able to benefit from the high temperatures. According to Dr. Ziegler, however, there is nothing to prevent further spread within Germany. "I think a spread to other areas of Germany is very likely," Dr. Ziegler said at the workshop.

West Nile virus in birds and horses

Bird species in Germany vary in their susceptibility to the virus. While most wild birds show no symptoms of infection, passeriformes (passerine birds) in particular, as well as raptors and owls, are susceptible to the virus and show varying, mostly nonspecific symptoms, which can lead up to death. In contrast to the USA, however, there have been no mass bird deaths in Germany due to West Nile virus. One explanation for this could be that migratory birds acquired basic immunity against the virus in their wintering sites, Dr. Ziegler explained. Commercial poultry do not appear to be at risk from West Nile virus. Dr. Ziegler and her team are currently investigating the suitability of farm poultry as sentinels for early detection of West Nile virus in an area.

Fig.2: West Nile virus was detected for the first time in Germany in 2018 in a Great Horned Owl from an aviary near Halle (Saale).

Horses can also become infected with West Nile virus. Of the infected animals, about 20-30% show symptoms and about 8% of infected horses develop severe neurological symptoms that can end in the death of the animal.

One of the vectors of the virus is Culex pipiens, also known as the common house mosquito. This mosquito species is widespread throughout Germany, even in urban regions, making control virtually impossible. A more appropriate approach to preventing infection in horses is vaccination. Currently, three vaccines are approved for horses and it is recommended to vaccinate horses in endemic areas before the start of the mosquito season.

There are no approved vaccines for humans yet, which also makes West Nile virus a challenge for the ÖGD, as Dr. Pantenburg pointed out in her presentation. For the public health sector, the West Nile virus is relevant both in terms of direct hazard prevention and in terms of prevention.

West Nile virus in humans

Humans can become infected with West Nile virus through mosquito bites, organ transplants, or blood transfusions. In 80% of cases, infection is asymptomatic. Only about 20% develop a febrile, flu-like illness called West Nile fever. About 1% of patients develop a severe disease with a neuroinvasive course that can be fatal.

In Germany, the first detected mosquito-borne West Nile virus infection in humans occurred in Leipzig in 2019. A total of five human cases were documented in 2019. In 2020, there were already 22 confirmed human cases in Germany. " We have to expect more autochthonous cases in 2021," Dr. Pantenburg said. West Nile virus infection is notifiable in Germany, but in view of the high rate of asymptomatically infected persons, the risk of a large number of unreported cases is high. One way to better estimate the seroprevalence in the population is to examine blood donations. These are now tested for the virus in endemic areas during the mosquito season (June to September) in Germany.

Challenges for the public health sector

For the public health sector, finding cases is not only a challenge due to the many asymptomatic cases, but also due to the time-consuming diagnostics, since a simple antibody detection in the serum of patients can lead to cross-reactions with other flaviviruses (by infection or vaccination) such as TBE virus, yellow fever virus, dengue virus or Japanese encephalitis virus.

According to Dr. Pantenburg, in order to meet the challenges posed by West Nile virus, cross-sector collaboration between clinical medicine, veterinary medicine and the public health sector in the sense of the One Health concept is indispensable. This could result in an application-oriented, evidence-based approach that would improve the handling of new zoonotic pathogens in Germany in the future.

The pandemic as an opportunity

"Even though the corona pandemic is currently tying up a lot of resources that are lacking elsewhere, the pandemic may also be an opportunity, as it brings the relevance of infection control into the awareness of politics and society and strengthens the networking of the public health sector and science," said Dr. Pantenburg. Her appeal to all participants to engage in cross-sectoral cooperation in the fight against new zoonoses arising from climate change in Germany was met with much approval.

Fig. 3: The One Health concept considers the connection of animal, human and environmental health and is therefore a necessary guideline in the fight against zoonoses in the context of climate change.

The workshop has shown how valuable the exchange between human and veterinary medicine, as well as the exchange between science and the public health sector can be. Especially with regard to emerging zoonoses, a joint approach and the exchange of experience and knowledge is an important factor to be able to react quickly. Climate change will probably bring more zoonoses to Germany in the next few years. Therefore, it seems all the more important to establish functioning networks for cross-sectoral cooperation now.

Text: Dr. Dana Thal

Further links: